One of the questions I’ve been carrying with me into teaching situations lately is how and when I feel the difference between being the structure and being the void—embodying articulation or the possibility of articulation and being the openness of reception. (Bear with me, I know neither are separate or pure!) A desire to distinguish between projective intelligences (i.e. I speak, I answer, I profess ideas or information) and receptive intelligences (i.e. I listen, I pause or hold silence, I ask emergent or responsive questions).1 For me, the difference between embodying structure or void, projective or receptive intelligence actually feels like a very fine line. In class, I know I make choices which initiate our collective action, even as I know chance as much as institutional prerogatives define some of the criteria for my choices. I negotiate too the fantasy that there are times when I speak in class that I am more directly (more only) myself.

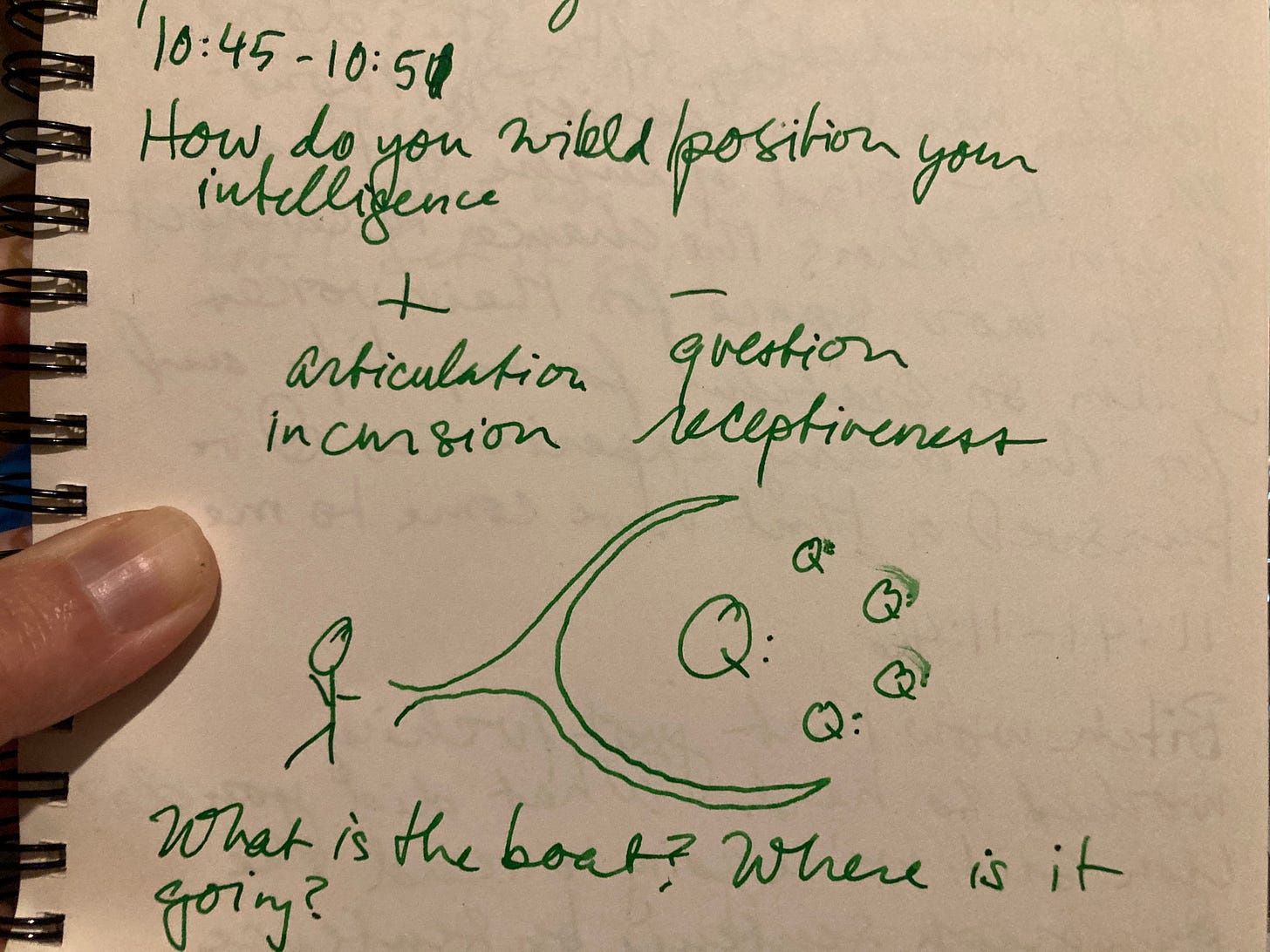

(A rough drawing during class time I have mixed feelings about.)2

The stakes for these questions have always felt high to me, but are particularly so when I work with these students at The Care Center—students who are sharp and sparkling full of knowledge and desire, wise feeling, and experience, who are most often significantly disempowered and disenfranchised because our education system and society at large is largely set up to punish people who drop out or are different somehow, particularly young people who decide to become mothers—students who have been bored or discouraged or crushed or shut out or dismissed or forgotten by most of the educational environments they’ve found themselves in—students often coming from places and people who have themselves been historically and systematically exploited and abused by racist and colonial states and citizens alike, with so much of that harm and violence becoming intergenerational.

Yesterday morning, as I made my way up the steps of The Care Center for the third time this summer, I noticed a chalk drawing on the porch and stopped to take a picture:

I felt myself follow the cracks toward a combined sense of self-observation, nascency, sacrifice, anticipation, immanence. Arms poised in a presentational listening or receiving mode, released and frozen in the gray surrender of a statue, stretched wide in welcome and desire for flight, desire to gather the world, light sweeping and shaping the forms. The staggering of life in time, all present, facing in one direction. I squatted down and felt like a child and a childless mother, full of creation, myself. I had not noticed this drawing on the previous two mornings, when I was probably too focused on the work that would follow my own arrival, and being on time.

It primed me in a deep weird way to allow time to be my own subject during the periods we wrote in class that day. Because when the class writes, I always write too. (This is one of the expectations of this program I was trained to teach in, but it is doubtless an ethical move made by plenty of teachers who actively facilitate writing in the space and time of class.) Arising from the need to open up the field of even more good questions inherent in Robin Kimmerer’s “Learning the Grammar of Animacy,” one of my several impossible five-minute questions during this session was Where does knowledge come from? Here is part of what I wrote:

I also really believe knowledge arises out of reflection on one’s experiences in time—that time is an essential part of the emergence of knowledge, and that very few of us have enough time for the reflection we need to recognize what we truly know.

One of the things I love about freewriting in class is that I allow myself to suspend the part of my intelligence that is overwhelmed by the magnitude of everything and just say things. Writing alongside other people helps me sidestep the beautiful terrible theoretically-inclined meatgrinder of my solitary consciousness, the one that atomizes me, that endlessly parses and complicates whatever it is I’m thinking about in what feels like an endless variety of directions. I have a different sense of being with in my writing when I’m doing it with other people. (I have so many more thoughts about my challenges with audience in writing that I’ll save for another time, though I have written some about it here.) But I’ve also realized that I feel a different kind of desire to be heard and understood by these amazing people I’m working with.

Controlling (or structuring or shaping) time is something teachers are expected to do, and maybe do, or try to do—the truth is, people in a room are always where they are, which could be elsewhere and another time! If you’re lucky enough to have a functioning clock in your classroom, you are checking it; but more likely that fucking cell phone is out and you’re poking it from time to time. (A terrible habit! I’ve promised myself to maintain my little Casio watch-wearing past my usual time in the woods and into my time in the boxes of the institution.) I find that time is incredibly precious in classes, and beyond my tendency to overplan, the very real need to actually slow down and do things—study and read and write and share things—at a pace that brings the complexity of the whole room along with you and together with itself means class feels shorter and shorter every year.

In the specific pedagogy of this program, I am supposed to write “scripts” for each day that are managed by the minute: primarily, number of minutes for reading aloud, writing or some other textual activity, and forms of sharing that can unfold between the individual and the full group or in pairs or smaller group. Discussion is meant to be minimized. What I appreciate and have learned from this approach pertains to my awareness of my own desire for a good conversation, inescapably from my own position, and when that desire ultimately results in certain kinds of speed and breadth and pitch of dialogue that might mean a limited number of students are actually participating. This work has also shaped my awareness of the value of writing as a form of thinking, one that remains to be interacted with in the future in a way that is different than conversation, or even collective notes on conversation.

My time with this group of people, three hours a day for two weeks, feels incredibly short, and also coincides totally with the present needs and struggles of all the people in the room. This is, of course, always true—but in some places context and performances make it easier (and often obligatory) to forget. There’s also a deep and present need for the emergence of a little bit of comfort and solidarity in the work we are doing together. And I tend to follow the group’s lead when these moments of connection and shared understanding arise.

In any case (and I mean any number of cases) letting go of the control of time in the classroom is one way a teacher can find themselves in a posture of reception, learning, losing their own sense of what the value of time is supposed to be. I think it’s a question that most teachers ask themselves: when should you release yourself and the event of the class from the immediate plan or from the larger objectives or directives that gird your periphery toward unexpected ends?

After a slightly delayed pizza lunch facilitated by our wonderful director Ann, my group reconvened in our room with not much time left in our day together. I faced a group of people who seemed happy and connected after two hours of work that morning, after doing a long passage-based writing exercise with the Kimmerer that had them partnered and writing first in response to each other and then in response to each other’s responses. I surveyed my own plan, printed and flat on the desk in front of me, and enacted a swerve. We would turn to the text I’d asked them to read, Dawn Lundy Martin’s “The Long Road to Angela Davis’s Library,” but we would forgo the series of prompts I’d composed the night before (see: “Loop writing”). Instead, not knowing what would happen, I offered that we would read the first paragraph of the essay aloud, and after each sentence we would pause, and anyone could ask any question they wanted. I promised to write these questions on the board. To my left, Rosalyn read the first sentence:

“Who’s to say when the turn from girl to woman happens, or what’s in between, in that fold, which one might also call a fount?”

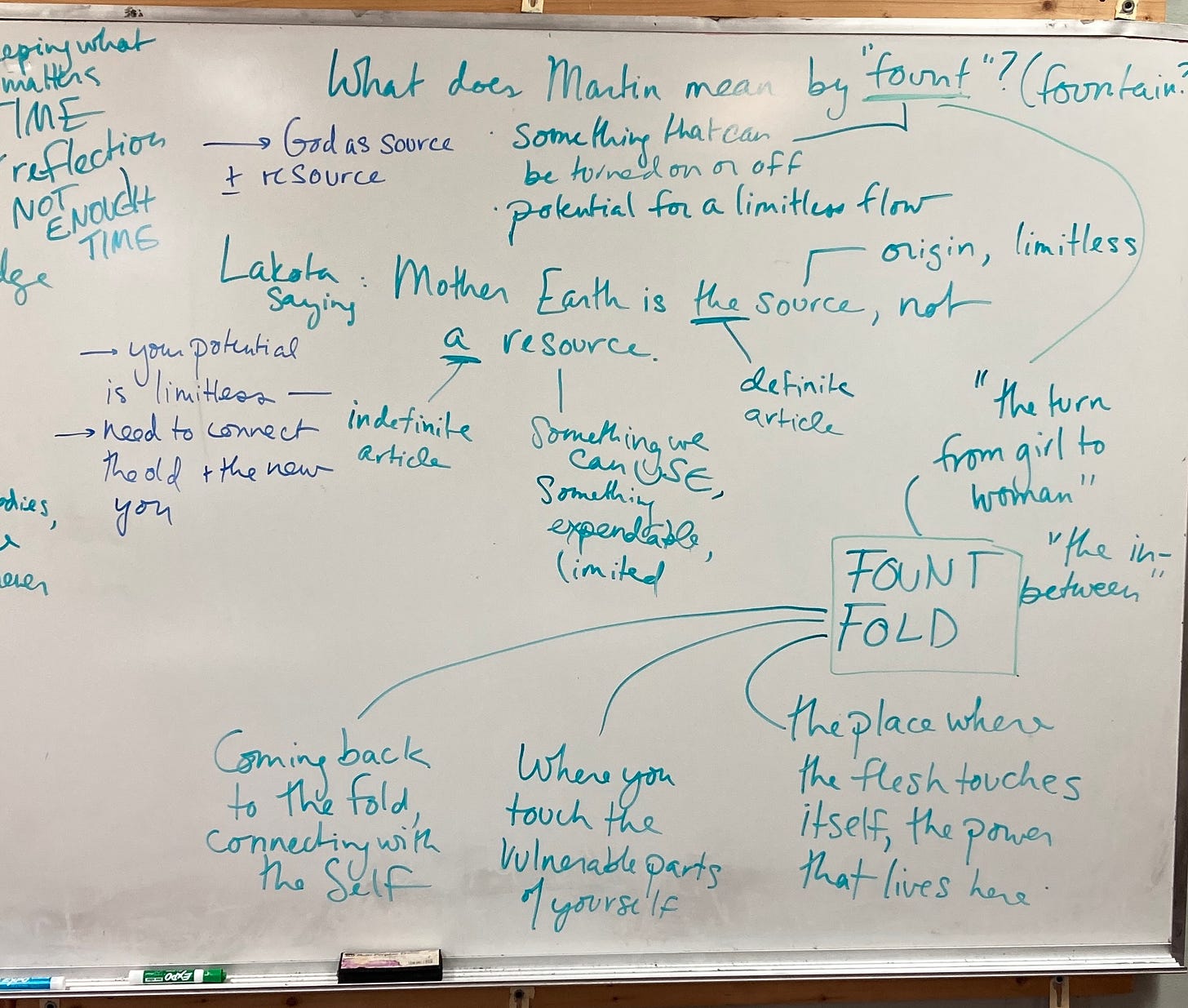

The first question was tossed out quickly, What does Martin mean by “fount”? Liz says that Siri told her the definition of fount was “a source of a desirable quality or commodity,” but when an abridged paper dictionary gets opened we find “fountain, source.” We briefly talk about the value of the time it takes to look a word up in a paper dictionary as opposed to a digital source. When is it worth it to do something that you know will take more time but will lead you somewhere good? I ask, and then take a moment to point to our work together over the past three days, and how we have been making more time to write than to talk about things. What is the difference you experience between having a group discussion about something and writing about it yourself? The group speaks about how in writing you can practice listening to yourself, creating a record, figuring out what you think before you interact with other people’s ideas. “It’s frustrating!” one student says. “I just want to talk it’s so much easier!” Another person acknowledges that they have surprised themselves by the places they’ve gone in the writing, and compares this to how, in speaking, they feel a lot of pressure to be relatable, understood.

We turn back to Martin’s essay: What do we already know about a fountain? and thoughts come out related to a fountain’s capacity to be turned on and turned off, and the illusion of a limitless flow. Gri offers a Lakota saying: “Mother Earth is the source, not a resource,” which guides us toward asking the question of the difference between the words “source” and “resource,” and their corresponding definite and indefinite articles. We eddy for a moment in the problem of seeing the earth’s capacities as “limitless.” Destiny returns us to the text by asking, What is coming out of that fountain? Why does Martin make the “in between” of girl and woman both a “fold” and a “fount”?

I made a deep fold in the center of a piece of paper and asked: What do we already know about a fold? One student spoke of the folds of her body, and the awareness that comes from self-touch. Another said: “To me, to fold is to bow out, to quit. I’m out!” And what followed was a conversation to which I cannot now do justice in writing—one through which senses of the erotic, creative power of bodies met the vulnerability of surrender or giving up, or hiding. And you can see, in the picture below, what I managed to record on the board, even as I was completely absorbed in the unfolding dialogue.

It was already 12:15 and we had only read a single sentence of the opening paragraph of Martin’s essay, sharing the space of many questions. Someone said, “I can’t believe how much we can say about a single sentence!” And then I invited us to write for ten minutes, continuing the conversation in our own thoughts, going places you wanted to go in conversation with the sentence that we didn’t have a chance to yet, and acknowledging that there was so much more that hadn’t yet been named or explored in this sentence, given the context of the essay.

Out of the writing, Rosalyn shared that reading this quote through her life experience had made her think about how God is both source and resource to her, something limitless and useful. Jess found a relationship between her hopeful feeling of the limitless potential in herself and the need to create a real connection between “the old you and the new you”—that potential emerges out of a sense of acceptance and understanding between them. But of course we ran out of time before more folks could share.

I left humbled by what happened in these final thirty minutes of class and also jazzed. I don’t want to explain away the beauty and the mystery of what happened, but I also don’t want to pretend that there aren’t things for me to learn here, or reflect on. Patience to acknowledge when I steered and when I followed. Questions about the value of exploding a single sentence, rather than sweeping through and responding to a greater portion of the text. When others headed in the direction I really wanted to go, whether it was back to the text, or toward questions and meaning I found myself aching toward; and when I was taught by the impulses and ideas of others.

UCH—whatever intelligence is!...and the way these projective and receptive intelligences find their observable ground (or not!) in the extensive apparatus that emanates from a teacher (syllabi, hand outs, assignments or prompts, etc.) or within the body of the teacher themselves (in voice, tone, volume, language, presence, etc.). This question of where teachers locate our intelligences when we are teaching will be the subject of another post!

This is a rough drawing emerging from a moment in class! I say to myself: Oh, don’t fool, you are also held by the question too. To the weird spontaneous questions “What is the boat? Where is it going?” I want to now add, Who built the boat? What is the medium and action for the movement of the boat? And how am I responsible to it?

“When is it worth it to do something that you know will take more time but will lead you somewhere good?” Oof, writing this one out for myself. Thank you!

Love your fan base here!